3 Limits

Both concepts of differentiation and integration are based on the idea of limit.

3.1 Introduction

Problem 1 Suppose an object moves along the \(x\)-axis and its displacement \(s\) in meters at time \(t\) in seconds is given by \[s(t)=t^2,~~~t\geq 0.\] Find its velocity at time \(t=2\).

Solution Velocity (or speed) is defined by \[\text{velocity}=\frac{\text{distance traveled}}{\text{time elapsed}}\]

| \(n\) | Time interval | Velocity |

|---|---|---|

| \(1\) | \([2,2.5]\) | \(4.5\) m/s |

| \(2\) | \([2,2.25]\) | \(4.25\) m/s |

| … | … | … |

| \(n\) | \([2,2+\frac{1}{2^n}]\) | \(4+\frac{1}{2^n}\) m/s |

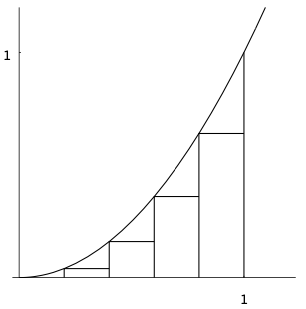

Problem 2 Find the area of the region that lies under the curve \(y=x^2\) and above the \(x\)-axis for \(x\) between \(0\) and \(1\).

Solution

Figure 3.1: Area under the curve

\[\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} S_n&=\frac{1}{n}\cdot 0+\frac{1}{n}\cdot\left(\frac{1}{n}\right)^2+\frac{1}{n}\cdot\left(\frac{2}{n}\right)^2+\ldots+\frac{1}{n}\cdot\left(\frac{n-1}{n}\right)^2 \\ &=\frac{1}{3}-\frac{1}{2n}+\frac{1}{6n^2} \end{aligned} \end{equation}\]

3.2 Limits of Sequences

Definition

A sequence is a function whose domain is \(\mathbb{Z}_+\).

A sequence of real numbers is a sequence whose codomain is $ $.

Illustration Let \(f:~ \mathbb{Z}_+\rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) be a sequence. For each positive integer \(n\), the value \(f(n)\) is called the \(n\)-th term of the sequence and is usually denoted by a small letter together with \(n\) in the subscript, for example \(a_n\). The sequence is also denoted by \((a_n)_{n=1}^\infty\).

Definition A sequency \((a_n)_{n=1}^\infty\) is said to be convergent if there exists a real number \(L\) such that \(a_n\) is arbitrarily close to \(L\) if \(n\) is sufficiently large. For simplicity, we will say \(a_n\) is close to \(L\) if \(n\) is large.

Remark In the definition of convergent, it is clear that if \(L\) exists, then it is unique. We say \(L\) is the limit of \((a_n)_{n=1}^\infty\) and write \(\underset{n\rightarrow\infty}{\lim}a_n=L\).

Rules for limits of sequences

\(\underset{n\rightarrow\infty}{\lim}k=k\)

\(\underset{n\rightarrow\infty}{\lim}\frac{1}{n^p}=0\), where \(p\) is a positive constant.

\(\underset{n\rightarrow\infty}{\lim}\frac{1}{b^n}=0\), where \(b\) is a positive constant greater than \(1\).

\(\underset{n\rightarrow\infty}{\lim}(a_n+b_n)=\underset{n\rightarrow\infty}{\lim}a_n+\underset{n\rightarrow\infty}{\lim}b_n\).

\(\underset{n\rightarrow\infty}{\lim}a_nb_n=\underset{n\rightarrow\infty}{\lim}a_n\cdot\underset{n\rightarrow\infty}{\lim}b_n\).

\(\underset{n\rightarrow\infty}{\lim}\frac{a_n}{b_n}=\frac{\underset{n\rightarrow\infty}{\lim}a_n}{\underset{n\rightarrow\infty}{\lim}b_n}\).

Example Find \(\underset{n\rightarrow\infty}{\lim}\left(4+\frac{1}{2^n}\right)\), if it exists.

Example Find \(\underset{n\rightarrow\infty}{\lim}\frac{2n^3-3n^2+n}{6n^3}\), if it exists.

Example Find \(\underset{n\rightarrow\infty}{\lim}(1+2n)\), if it exists.

Example Find \(\underset{n\rightarrow\infty}{\lim}\frac{n+1}{2n+1}\), if it exists.

3.3 Limits of Functions at Infinity

Definition Let \(f\) be a function such that \(f(x)\) is defined for sufficiently large \(x\). Suppose \(L\) is a real number satisfying the following condition: \(f(x)\) is arbitrarily close to \(L\) if \(x\) is sufficiently large. Then we say that \(L\) is the limit of \(f\) at infinity and write \(\underset{n\rightarrow\infty}{\lim}f(x)=L\).

Remark

The condition \(f(x)\) is defined for sufficiently large \(x\) means that there is a real number \(r\) such that \(f(x)\) is defined for all \(x>r\).

\(L\) is called the limit because it is unique if it exists.

For simplicity we will say \(f(x)\) is close to \(L\) if \(x\) is large.

Rules for limits of functions at infinity

\(\underset{x\rightarrow\infty}{\lim}k=k\)

\(\underset{x\rightarrow\infty}{\lim}\frac{1}{x^p}=0\), where \(p\) is a positive constant.

\(\underset{x\rightarrow\infty}{\lim}\frac{1}{b^x}=0\), where \(b\) is a positive constant greater than \(1\).

\(\underset{x\rightarrow\infty}{\lim}(f(x)\pm g(x))=\underset{x\rightarrow\infty}{\lim}f(x)\pm \underset{x\rightarrow\infty}{\lim}g(x)\).

\(\underset{x\rightarrow\infty}{\lim}(f(x)\cdot g(x))=\underset{x\rightarrow\infty}{\lim}f(x)\cdot\underset{x\rightarrow\infty}{\lim}g(x)\).

\(\underset{x\rightarrow\infty}{\lim}\frac{f(x)}{g(x)}=\frac{\underset{x\rightarrow\infty}{\lim}f(x)}{\underset{x\rightarrow\infty}{\lim}g(x)}\).

Example Find the following limits if they exist.

\(\underset{x\rightarrow\infty}{\lim}\left(1-\frac{2}{x^3}\right)\)

\(\underset{x\rightarrow\infty}{\lim}\left(2^{-x}+3\right)\)

\(\underset{x\rightarrow\infty}{\lim}\frac{x^2+1}{3x^3-4x+5}\)

\(\underset{x\rightarrow\infty}{\lim}\frac{x^3+1}{3x^3-4x+5}\)

Leading terms rule Let \(f(x)=a_nx^n+\cdots+a_1x+a_0\) and \(g(x)=b_mx^m+\cdots+b_1x+b_0\), where \(a_n\neq 0\) and \(b_m\neq 0\). Then we have \[\underset{x\rightarrow\infty}{\lim}\frac{f(x)}{g(x)}=\underset{x\rightarrow\infty}{\lim}\frac{a_nx^n}{b_mx^m}.\]

Remark

If \(n=m\), the limit is \(\frac{a_n}{b_n}\).

If \(n<m\), the limit is \(0\).

If \(n>m\), the limit does not exist.

The Leading terms rule can’t be applied to limits of rational functions at a point: \(\underset{x\rightarrow a}{\lim}\frac{f(x)}{g(x)}\), where \(a\in\mathbb{R}\).

Sandwich Theorem Let \(f,g\) and \(h\) be functions such that \(f(x)\), \(g(x)\) and \(h(x)\) are defined for sufficiently large \(x\). Suppose that \(f(x)\le g(x)\le h(x)\) if \(x\) is sufficiently large and that both \(\underset{x\rightarrow a}{\lim}f(x)\) and \(\underset{x\rightarrow a}{\lim}h(x)\) exist and are equal (with common limit denoted by \(L\)). Then we have \(\underset{x\rightarrow a}{\lim}g(x)=L\).

Example Find \(\underset{x\rightarrow a}{\lim}\frac{\sin x}{x}\), if it exists.

Infinite limits Let \(f\) be a function such that \(f(x)\) is defined for sufficiently large \(x\). Suppose that \(f(x)\) is arbitrarily large if \(x\) is sufficiently large. Then we write \(\underset{x\rightarrow \infty}{\lim}f(x)=\infty\). Because \(\infty\) is not a real number, \(\underset{x\rightarrow \infty}{\lim}f(x)=\infty\) does not mean the limit exists. In fact, it indicates that the limit does not exist and explains why it does not exist.

Example \(\underset{x\rightarrow \infty}{\lim}(1+x^2)=\infty\). \(\underset{x\rightarrow \infty}{\lim}(1-x^2)=-\infty\)

Limits at negative infinity Similar to limits at infinity, we may consider limits at negative infinity provided that \(f(x)\) is defined for \(x\) sufficiently large negative.

Example \(\underset{x\rightarrow -\infty}{\lim}\frac{1}{x}=0\). \(\underset{x\rightarrow -\infty}{\lim}x^3=-\infty\). \(\underset{x\rightarrow -\infty}{\lim}(1-x^3)=\infty\)

3.4 One-sided Limits

Right-side limits Let \(a\in\mathbb{R}\) and let \(f\) be a function such that \(f(x)\) is defined for \(x\) sufficiently close to and greater than \(a\). Suppose \(L\) is a real number satisfying that \(f(x)\) is arbitrarily close to \(L\) if \(x\) is sufficiently close and greater than \(a\). Then we say that \(L\) is the right-side limit of \(f\) at \(a\) and we write \(\underset{x\rightarrow a+}{\lim}f(x)=L\).

Remark In the definition, it doesn’t matter whether \(f\) is defined at \(a\) or not. If \(f(a)\) is defined, its value has no effect on the existence and the value of \(\underset{x\rightarrow a+}{\lim}f(x)\). This is because right-side limit depends on the values of \(f(x)\) for \(x\) close to and greater than \(a\).

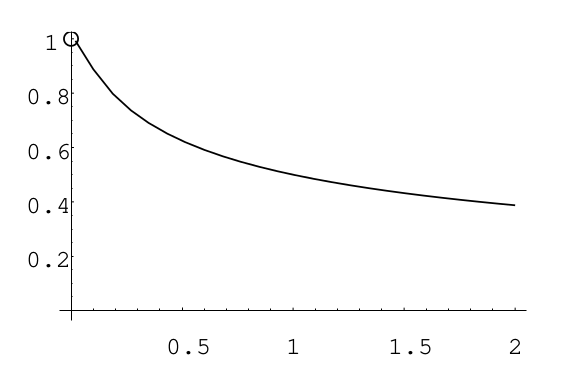

Example \(f(x)=1-2^{-\frac{1}{\sqrt{x}}}\).

Figure 2.1: Figure of f(x)

Left-side limits If a function \(f\) is defined on the left-side of \(a\), we can consider its left-side limit. The notation \(\underset{x\rightarrow a-}{\lim}f(x)=L\) means that \(f(x)\) is arbitrarily close to \(L\) if \(x\) is sufficiently close to and less than \(a\).

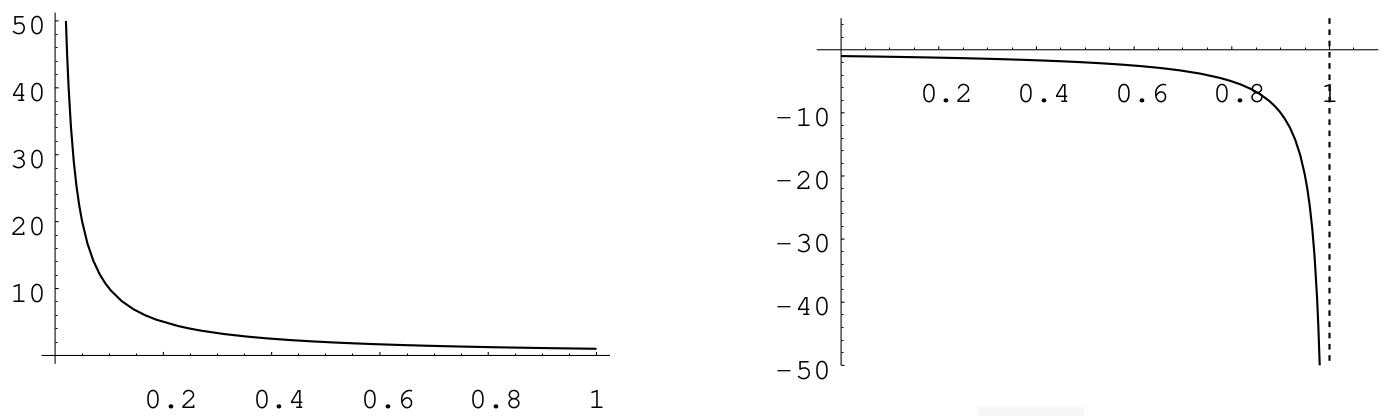

Example If the one-sided limit (approaching to \(a\)) is infinity, then the line \(x=a\) is a vertical asymptote for the graph of \(f\).

\(\underset{x\rightarrow 0+}{\lim}\frac{1}{x}=\infty\).

\(\underset{x\rightarrow 1-}{\lim}\frac{1}{x-1}=-\infty\).

Figure 2.2: Figure of f(x)

3.5 Two-sided Limits

Definition Let \(a\in\mathbb{R}\) and let \(f\) be a function that is defined on the left-side and right-side of \(a\). Suppose that both \(\underset{x\rightarrow a-}{\lim}f(x)\) and \(\underset{x\rightarrow a+}{\lim}f(x)\) exist and are equal (with the common limit denoted by \(L\) which is a real number). Then the two-sided limit, or more simply, the limit of \(f\) at \(a\) is defined to be \(L\), written \(\underset{x\rightarrow a}{\lim}f(x)=L\).

Example Let \(f(x)=\frac{x}{|x|}\). \(\underset{x\rightarrow 0}{\lim}f(x)\) does not exist.

Rules for limits of functions at a point

\(\underset{x\rightarrow a}{\lim}k=k\)

\(\underset{x\rightarrow a}{\lim}x^n=a^n\), where \(a\in\mathbb{R}\) and \(n\) is a positive constant.

\(\underset{x\rightarrow a}{\lim}{b^x}=b^a\), where \(a\in\mathbb{R}\) and \(b\) is a positive constant.

\(\underset{x\rightarrow a}{\lim}(f(x)\pm g(x))=\underset{x\rightarrow a}{\lim}f(x)\pm \underset{x\rightarrow a}{\lim}g(x)\).

\(\underset{x\rightarrow a}{\lim}(f(x)\cdot g(x))=\underset{x\rightarrow a}{\lim}f(x)\cdot\underset{x\rightarrow a}{\lim}g(x)\).

\(\underset{x\rightarrow a}{\lim}\frac{f(x)}{g(x)}=\frac{\underset{x\rightarrow a}{\lim}f(x)}{\underset{x\rightarrow a}{\lim}g(x)}\).

Theorem Let \(p(x)\) be a polynomial and let \(a\) be a real number. Then we have \[\underset{x\rightarrow a}{\lim}p(x)=p(a)\]

Theorem Let \(p(x)\) and \(q(x)\) be polynomials and let \(a\) be a real number. Suppose that \(q(a)\neq 0\). Then we have \[\underset{x\rightarrow a}{\lim}\frac{p(x)}{q(x)}=\frac{p(a)}{q(a)}.\]

Example Find \(\underset{x\rightarrow 4}{\lim}(1+x^2)\), if it exists.

Example Find \(\underset{x\rightarrow 1}{\lim}\frac{x-1}{x^2+x-2}\), if it exists.

Example Find \(\underset{x\rightarrow 1}{\lim}\frac{x+1}{x^2+x-2}\), if it exists.

Example Let \(f(x)=x^2+3\). Find \(\underset{h\rightarrow 0}{\lim}\frac{f(x+h)-f(x)}{h}\).

3.6 Continunous Functions

Definition Let \(a\in\mathbb{R}\) and let \(f\) be a function such that \(f(x)\) is defined for \(x\) sufficiently close to \(a\) (including a). If the following condtion holds, \[\underset{x\rightarrow a}{\lim}f(x)=f(a),\] then we say that \(f\) is continuous at \(a\). Otherwise, we say that \(f\) is discontinuous at \(a\).

Remark Since \(\underset{x\rightarrow a}{\lim}x=a\), we have \(\underset{x\rightarrow a}{\lim}f(x)=f\left(\underset{x\rightarrow a}{\lim}x\right)\). If we consider \(f\) and \(\lim\) as two operations, it means that the operation of taking \(f\) and that of taking limit commute. That is the order of taking \(f\) and taking limit can be interchanged.

Remark If a function \(f\) is undefined at \(a\), it is meaningless to talk about whether \(f\) is continuous at \(a\). The condition in the definition means that (1) the limit exists and (2) the limit equals to \(f(a)\).

Example Let \[\begin{equation} f(x)= \begin{cases} -1 ~~&\text{if}~~x<0 \\ 0 ~~&\text{if}~~x=0\\ 1 ~~&\text{if}~~x>0 \end{cases} \end{equation}\] Determine whether \(f\) is continuous at \(0\) or not.

Definition Let \(I\) be an open interval and let \(f\) be a function defined on \(I\). If \(f\) is continuous at every \(a\in I\), then we say that \(f\) is continuous on \(I\).

Example Let \(f(x)=\frac{1}{x}\). Show that \(f\) is continuous on \((0,\infty)\) as well as on \((-\infty,0).\)

Remark Geometrically, a function \(f\) is continuous on an open interval \(I\) means that the graph of \(f\) on \(I\) has no breaks; if we use a pen to draw the graph on paper, we can draw it continuously without raising the pen above the paper.

Theorem Every polynomial function is continuous on \(\mathbb{R}\).

Theorem Every rational function is continuous on every open interval contained in its domain.

Definition Let \(a\) be a real number and let \(f\) be a function defined on the right-side of \(a\) as well as at \(a\). If \(\underset{x\rightarrow a+}{\lim}f(x)=f(a)\), then we say that \(f\) is right-continuous at \(a\).

Definition Let \(a\) be a real number and let \(f\) be a function defined on the left-side of \(a\) as well as at \(a\). If \(\underset{x\rightarrow a-}{\lim}f(x)=f(a)\), then we say that \(f\) is left-continuous at \(a\).

Definition Let \(I\) be an interval in the form \([c,d)\) where \(c\) is a real number and \(d\) is \(\infty\) or a real number greater than \(c\). Let \(f\) be a function defined on \(I\). We say that \(f\) is continuous on \(I\) if it is continuous at every \(a\in(c,d)\) and is right-continuous at \(c\).

Definition Let \(I\) be an interval in the form \((c,d]\) where \(c\) is \(-\infty\) or a real number less than \(d\) and \(d\) is a real number. Let \(f\) be a function defined on \(I\). We say that \(f\) is continuous on \(I\) if it is continuous at every \(a\in(c,d)\) and is left-continuous at \(d\).

Definition Let \(I\) be an interval in the form \([c,d]\) where \(c\) and \(d\) are real numbers and \(c<d\). Let \(f\) be a function defined on \(I\). We say that \(f\) is continuous on \(I\) if it is continuous at every \(a\in(c,d)\) and is right-continuous at \(c\) and left-continuous at \(d\).

Example Let \(f:\mathbb{R}\rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) be the function given by \[\begin{equation} f(x)= \begin{cases} |x|~~&\text{if}~~-1\le x\le 1,\\ -1~~&\text{otherwise.} \end{cases} \end{equation}\] Discuss whether \(f\) is continuous on \([-1,1].\)

Intermediate value theorem Let \(f\) be a function that is defined and continuous on an interval \(I\). Then for every pair of elements \(a\) and \(b\) of \(I\), and for every real number \(\eta\) between \(f(a)\) and \(f(b)\), there exists a number \(\xi\) between \(a\) and \(b\) such that \(f(\xi)=\eta\).

Corollary Let \(f\) be a function that is defined and continuous on an interval \(I\). Suppose that \(a\) and \(b\) are elements of \(I\) such that \(f(a)\) and \(f(b)\) have opposite signs. Then there exists \(\xi\) between \(a\) and \(b\) such that \(f(\xi)=0\).

Corollary Let \(f\) be a function that is defined and continuous on an interval \(I\). Suppose that \(f\) has no zero in \(I\). Then \(f\) is either always positive in \(I\) or always negative in \(I\).

Example Find the solution set to the inequality \(x^3+3x^2-4x-12\le 0\).

Extreme value theorem Let \(f\) be a function that is defined and continuous on a closed and bounded interval \([a,b]\). Then \(f\) attains its maximum and minimum in \([a,b]\), that is, there exist \(x_1,x_2\in[a,b]\) such that \[f(x_1)\le f(x)\le f(x_2)\] for all \(x\in[a,b]\).

Example Let \(f:(0,1)\rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) be the function given by \[f(x)=\frac{1}{x}\]. It is straightforward to show that \(f\) is continuous on \((0,1)\). However, the function \(f\) does not attain its maximum nor minimum in \((0,1)\).

Example Let \(f:[0,1]\rightarrow \mathbb{R}\) be the function given by \[\begin{equation} f(x)= \begin{cases} 1~~&\text{if}~~x=0\\ \frac{1}{x}~~&\text{if}~~0<x\le 1. \end{cases} \end{equation}\] The function \(f\) does not attain its maximum in \([0,1]\).